Our news analysis on the end of 'Australian' house prices and what the future holds for brokers

House prices have peaked, recent figures suggest, and the phenomenal growth of the past year now appears unsustainable. Sam Richardson investigates what the future holds for brokers

Spring, for the housing market, has perhaps better resembled the build-up to a monsoon. From Reserve Bank governor Glenn Stevens’ comments in July onwards, it seems the tension has mounted, with prices rising at faster and faster levels, debt-to-income ratios spiralling, and brokers processing ever more impossible volumes. Now the storm has finally broken, and news of falling loan volumes is reminding investors and brokers that the housing market is indeed ‘unbalanced’, but in a far more comprehensive way than Stevens’ use of the term suggested.

October’s ABS report, showing a 1.2% drop in the value of new property loans in August, also revealed a number of underlying trends that threaten to fragment the market. Even if November’s update shows a slight improvement (such are the perils of writing a monthly magazine), the divide between investors and owner-occupiers, domestic and foreign, metropolitan and regional will continue to grow.

We’ve drawn on the latest figures and asked leading economists and of course top brokers what the volatility of the past months means for brokers’ business.

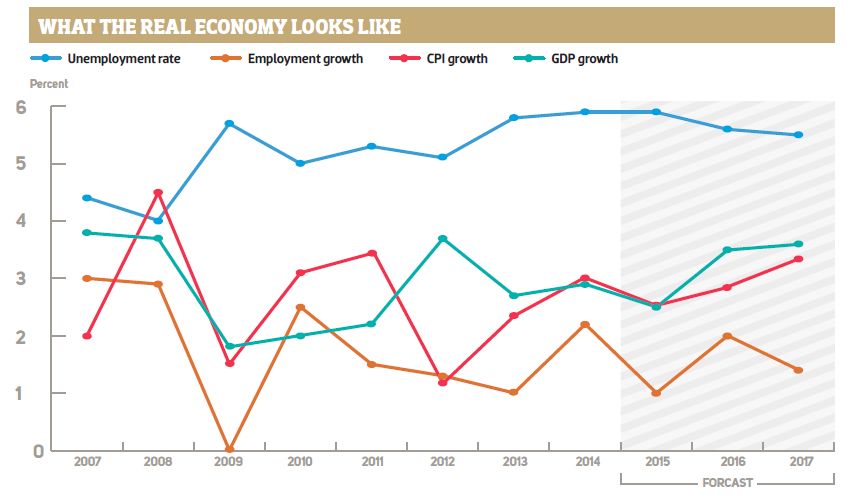

What the real economy looks like

INVESTORS AND THE BLAME GAME

Ostensibly, it all started in Hobart on 3 July when Stevens told a conference of economists that “investors should take care” in the Sydney market. He warned: “People should not assume that prices always rise. They don’t; sometimes they fall.”

Media focus has changed little since then, with good reason: refinancing aside, the proportion of loans going to investors hit 49.7% in August. “This is the highest share on record,” ANZ economist David Cannington told the Sydney Morning Herald. “It has risen from around 40% when the RBA started cutting rates in November 2011.”

Clearly, investors are not all the same, and public opinion is a poor guide to the sector. “Foreign investors are probably responsible for between 5% and 10% of investment purchases; “self-managed super funds probably about 3% of purchases; and negative gearing, which is the biggie, is responsible for probably 70–80% of investor property,” insists Martin North, principal of research firm Digital Finance Analytics (DFA). But abandoning negative gearing would cause ‘havoc’, Aussie Home Loans chief John Symond recently told Australian Broker.

It’s obvious that investors are driving out first home buyers, who now have their lowest share of the market since records began. More surprising, as AMP chief economist Shane Oliver reminds us, investors and first home buyers can be difficult to separate: ‘rentvestors’ purchase first investments ahead of first homes while continuing to rent. Perhaps the plight of rentvestors – competing with far wealthier investors – goes some way towards explaining August’s 0.1% fall in the value of new investment loans. But that explanation doesn’t go far enough – we need to look at the wider economy.

WHAT’S DRIVING INVESTMENT?

WHAT’S DRIVING INVESTMENT?

Australia’s housing market is less of a bubble and more of a greenhouse: built on reasonably solid foundations, it does a good job of trapping heat. But when we look out of the window we can see that the Australian economy has had nothing but rain (metaphorically speaking) for some time now. Australia’s ‘misery index’ – a sum of employment and inflation rates – is at its highest level since 2008, after wages declined relative to inflation for the second year in a row, and the IMF rates Australian house prices as the third most overvalued on earth. “House prices,” argues DFA’s North, “are out of kilter with any measure you choose to think about”.

Rising unemployment, forecast by BIS Shrapnel to go from 6.1% in August to 6.3% by the end of this year, is one of many reasons why the Reserve Bank has been so reluctant to raise interest rates in response to house prices. Instead they have resorted to what commentators term ‘jawboning’ (veiled threats), with RBA assistant governor Dr Malcolm Edey telling the Senate on 2 October that “I expect there will be … an announcement before the end of the year” regarding interest rates. Potential macroprudential tools are subject to similar uncertainties: penalising investors while protecting first home buyers and cooling some but not all regions is easier said than done.

Yet jawboning seems to be working, in that it is making potential investors take notice of the world beyond the housing market. One indication of this is the recent Westpac/Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment, which recorded an alarming 4.6% fall in the month of September. Although the proportion of respondents expecting house prices to rise increased, there was an 8.2% fall in those believing that now is the ‘time to buy a dwelling’, a 23% drop from last year. Crucially, says chief economist Bill Evans, “respondents remain nervous around the labour market”.

The original and long-term aim of low interest rates was not to benefit investors only but instead to boost the construction industry. “The last thing the Reserve Bank wants,” CommSec’s Savanth Sebastian told Australian Broker TV, “is [to] curb development.” Now numbers suggest development is picking up: the performance index of the Australian Industry Group/Housing Industry Association hit a nine-year high in September, led by house building. And QBE’s recently released Australian Housing Outlook optimistically claims that the level of new home commencements – ie supply – is now above the level of demand in all states except Queensland.

Housing deficiency is therefore starting to be tackled, but the sheer size of the supply-demand gap in certain states will mean development won’t reduce prices for years (until around 2016/17 according to QBE’s report). If for some reason no more houses came up for sale, explains CommSec’s Sebastian, Sydney would “effectively run out of the stock that’s for sale in 1.8 months”. So construction could explain price correction in the long term, but the decline in the value of loans recorded by the ABS seems to have come a few years early.

A NATION DIVIDED

So far this article has referred to the Australian housing market, but in practice there’s no such single entity. Over the past 12 months Sydney’s house prices have grown by 14.3%, Melbourne’s by 8.1%, and all other capitals by an average of just 4.8%, according to RP Data’s CoreLogic September report. Just as house prices seem to be detached from the real economy, Sydney’s housing market seems to have detached itself from the rest of Australia, and is heading in a very different direction.

MPA spoke to two expert brokers based less than three hours away from each other but who have had very different experiences: Raymond Xue of Sydney CBD-based ACA Mortgage Solution, and Laurie Parkes of Bathurst’s FrontRunner Finance Solutions. Xue has had a record-breaking year in all senses, writing $247m worth of loans. In contrast, says Parkes: “What is going on in Sydney is not being translated into Bathurst at all. We’re going through a quiet period. Since October last year we’ve only been doing average business … there’s certainly no boom going on here; if anything it’s slowed down a little bit. It’s extraordinary, considering low interest rates.”

Interestingly, Bathurst used to be prime investor turf, Parkes says. “I might be wrong, but I think it’s a lack of confi dence. Bathurst is a city where investment has been really good; it’s a university town.”

You might also expect a trickle-down effect between the two areas as overpriced Sydneysiders look for cheaper property in surrounding regional suburbs. Undoubtedly, given fundamental questions of land supply and demand, you wouldn’t expect Bathurst investor appetite to keep pace with Sydney’s, but you also wouldn’t expect the two cities to go in such different directions.

Xue is confident of growth for the next two to three years, until housing development makes a serious impact on Sydney’s housing deficiency. The reason? His Chinese clients won’t be affected by natural correction or RBA measures; they’re guided by wider international developments.

“At the moment, dollars are low in comparison to Chinese money, so more money will come to Australia,” Xue says. “Chinese property is not as good as before, so they’re thinking of buying property elsewhere to diversify their risk … with this trend, I can’t see any signs of slowdown.”

The Rise of the Two-Speed Housing Market

GO YOUR OWN WAY

A two-speed economy is emerging, between the vast majority of Australia where housing is starting to reflect economic realities, and Sydney and Melbourne where it reflects international trends. Although we can expect the latter cities to dominate top-volume lists over the next few years, quality brokers outside these areas may also have reasons for confidence. With housing becoming less of a guaranteed money-maker, it’ll give certain brokers, and certain areas, a chance to distinguish themselves. Take the example of Tiffen and Co., a brokerage based in Canberra. By the numbers, Australia’s capital has a relatively quiet housing market, with prices rising just 1.7% over the last year, the weakest increase of all capitals. Yet Gerard Tiffen is highly optimistic. “The residential market is really booming along … clearance rates are going through the roof,” he says.

Although units are struggling in Canberra, renovation finance is beginning to play a more important role, Tiffen says. “It’s a big part of our business right now, and it’s really changed dramatically over the last six to eight months … we’re not targeting that market, but we find more and more people are falling into it.”

Bryan Coleman of Priority Home Loans adds another voice to the debate. His stomping ground, Tamworth, in regional NSW, is doing surprisingly well. “We are enjoying some of the return to confidence in the economy … prices here are just so much better than Sydney it’s just ridiculous. It asks the question for people: why wouldn’t you try to move to a county area? It’s just so much more affordable to live.”

Broking in a place like Tamworth requires a deep understanding of the local economy. “[Confidence] is driven by different things here: if it doesn’t rain here, people aren’t confident … it’s devastating. We’ve got a lot of mining industry that’s growing here, and that pushes the market up,” says Coleman.

Finally, it would also be wrong to assume that the increase in foreign investors is a phenomenon exclusive to Sydney and Melbourne. “Chinese buyers are discovering Brisbane,” declared September’s McGrath Report, and Xue agrees. “If I have a chance I want to expand to Queensland in the next two years; it’s going to boom up. Sydney prices are too high.”

Another broker who specialises in foreign clients, Kiran Thapa of CAPKON – Property Investment Specialists, says Darwin is his biggest client base outside of Sydney, and he’s organising seminars in Dubbo, Wagga Wagga and other regional areas in NSW.

Ignore the cynics: we’re not at a tipping point, but we are at a crossroads. A two-speed housing market might seem bewildering to brokers (and frustrating to regulators), but it gives the rest of Australia a chance to leave the sweltering greenhouse of Sydney-Melbourne prices and actually reflect the real economy.

In the long term, perhaps this is a more sustainable situation that gives good brokers a chance to distinguish themselves, even if the short term may seem like a rude awakening.

Gerard Tiffen sums up the situation well: “I think people just keep using brokers and going [direct] to the banks less and less. So our market share is growing, even though maybe the pie is getting a little smaller.”

This issue is from Mortgage Professional Australia's December issue. Get the issue to read more!